Catherine Barnard*

An integral part of our European way of life is our values. … We Europeans can never accept Polish workers being harassed, beaten up or even murdered on the streets of Harlow. The free movement of workers is as much a common European value as our fight against discrimination and racism.

Jean Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission

State of the Union address, 14 Sept 2016

Free movement of persons v. free movement of workers

The context

While those voting Leave did so for many and various reasons, it is widely accepted that fears about migration were a significant driving factor - concerns that were fanned by an increasingly Eurosceptic press. For example, Lord Ashcroft’s polling indicates that one third of Leave voters said the main reason for their vote was that leaving ‘offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders’.

The question of how to control migration became a major issue during the referendum campaign. Take, for example, the views of Migration Watch, which is a think tank that believes that ‘sustainable levels of properly managed immigration are of distinct benefit to our society’. It argued:

At present immigration is neither sustainable nor well managed. In 2015 net migration was over 300,000. If net migration continues at recent levels the latest ONS [Office for National Statistics] statistics project that our population will increase by 500,000 per year - the equivalent of a new city the size of Liverpool every year.

There are about 3 million EU nationals living in the UK, although the National Insurance Number (NINO) data suggest that this might be an underestimate. The pull factors are not benefits, contrary to widely held public beliefs, but unemployment and low wages in home countries especially in Spain, Italy and Portugal and the EU-8 (Central and Eastern European) states. In its conclusion, the Office for National Statistics says ‘net migration remains at record levels although the recent trend is broadly flat’.

The capacity in which EU migrants move

Although EU migrants are often referred to as a homogenous group, they are in fact living and working in the UK in different legal capacities. As Migration Watch points out:

Free movement was originally designed for workers and the self-employed to take up work in another EU country. This was gradually expanded to include job seekers, students and those of independent means. Meanwhile, case law has removed the requirement to be economically active.

This systematic removal of restrictions on EU migration coincided with an expansion of the EU to less wealthy countries with the result that the number of people migrating grew very substantially.

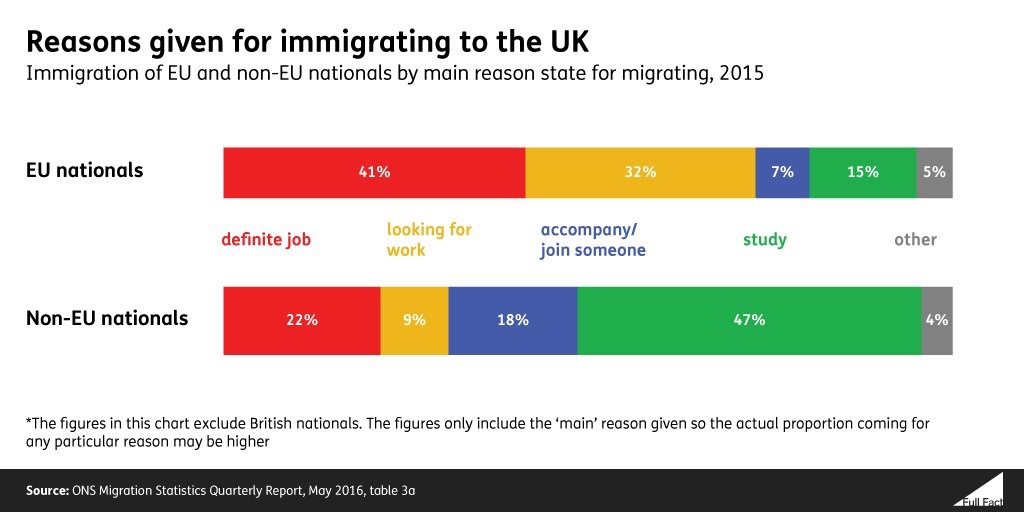

The percentage of EU nationals coming to the UK in some of these different capacities can be seen in the following diagram produced by the independent fact checking charity, FullFact:

270,000 EU nationals came to the UK last year (as compared to 277,000 non-EU nationals). Of those coming from the EU, 41% of the population came to the UK with a definite job already in hand; 32% came looking for work.

If the UK wants to retain full membership of the Single Market post-Brexit, the rhetoric is clear: it must continue to respect free movement of persons. Yet, for those voting Leave, that is one of the least palatable aspects of the Single Market. Would reconfiguring free movement of persons be a way to square the circle?

Focusing on migrant workers combined with some sort of emergency brake

One possibility would be for the UK to argue that free movement should be enjoyed only by the economically active, namely workers (but only those who already had a job) and the self-employed. If work seekers (whose right to move was first expressly recognised by the Court of Justice in Case C–292/89 R. v. IAT, ex p. Antonissen [1991] ECR I–745) were excluded from the right to free movement, this would reduce immigration figures by over 30%. This might make free movement of persons a more attractive proposition and help to meet the demands of business in a variety of sectors (care, distribution, agriculture, higher education) for EU migrant labour. (Students should also have rights of free movement but as an independent category. They should be removed from the global immigration statistics since many do not stay beyond the end of their course.)

The focus on restricting migration to the economically active was alluded to in the Spaak Report which pre-dated the drafting of the Treaty of Rome. The Report said:

une interpretation correcte de la notion de libre circulation des travailleurs: il comporte Ie droit de se presenter dans tout pays de Ia Communaute aux emplois effectivement offerts et de demeurer dans ce pays, si un emploi est effectivement obtenu, sans aucune restriction qui ne s’applique de la mȇme manière aux travailleurs nationaux eux-mȇmes;

More than sixty years later, the UK’s New Settlement Decision, negotiated in Brussels on 18-19 February 2016, but now defunct following the Brexit vote, also focused on the rights of free movement of the economically active:

Free movement of workers within the Union is an integral part of the internal market which entails, among others, the right for workers of the Member States to accept offers of employment anywhere within the Union. [emphasis added]

Further, while the Prime Minister did not get the express emergency brake on migration that he might have hoped for in February (the brake applied only to in-work benefits), a close reading of the text suggests that other EU leaders acknowledged space for restricting migration:

It is legitimate to take [the different levels of remuneration between Member States and different levels of remuneration] into account and to provide, both at Union and at national level, and without creating unjustified direct or indirect discrimination, for measures limiting flows of workers of such a scale that they have negative effects both for the Member States of origin and for the Member States of destination. [emphasis added]

The point was made forcibly elsewhere in the Decision:

Free movement of workers may be restricted by measures proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued. Encouraging recruitment, reducing unemployment, protecting vulnerable workers and averting the risk of seriously undermining the sustainability of social security systems are reasons of public interest recognised in the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

This seems to have been a fairly major concession to the UK: EU migration rights restricted to those who are economically active but with the possibility of some sort of brake (possibly at regional and not just national level) if the lid on the pressure cooker is showing signs of blowing. It is surprising that David Cameron did not trumpet his achievement here more loudly.

The issues surrounding the proposal to restrict EU migration to those economically active

The proposal to restrict EU migration to those who are economically active is easy to state but harder to deliver. There are two particular problems: proof of worker status and exploitation. In respect of proof of workers status, the risk is that the Tier 2 visa status which is granted to non-EU migrant workers would have to be extended to EU workers. I would argue not: the visa regime is onerous for employers. An easier mechanism would be to use the process for registering for a national insurance number and extend it to granting registration for a work permit on proof of an offer of employment; a simple and low intensive sifting process. Employers would then simply need to check that an individual has been through this process.

Of more concern is the second point, namely the possibility of exploitation of vulnerable EU workers by gangmasters or unscrupulous agencies. These bodies already have well-established mechanisms for recruiting low-skilled staff in Poland, Latvia and elsewhere. Many workers are brought to the UK to work on farms and in food processing plants. Some are housed in low quality accommodation owned by gangmasters and their passports are removed so they cannot leave. This is where robust enforcement of employment rights becomes essential. The Modern Slavery Act is a good starting point but does not cover less extreme forms of abuse. More support to the Gangmasters Licensing Authority and an expansion of its brief would help to address these issues.

Conclusions

Restricting migration to job-holding workers would be a step towards maintaining free movement of persons while also responding to a perceived need to control migration. President Juncker’s reference to free movement of workers in his State of the Union address, cited at the beginning of this blog, might be a hint as to a possible way forward. If the results of a poll for British Future accurately reflect the views of the wider public, there may be some merit in this idea. The poll found:

- Only 12% of people would like to see a reduction in the numbers of highly skilled workers migrating to Britain; nearly four times as many (46%) would like to see more of it, with 42% saying that it should stay the same. Among people who voted Leave in the referendum these numbers remain broadly the same: 45% would like to see an increase, 40% say that the numbers should stay as they are and just 15% would like to see them reduced.

- People are less positive about low-skilled workers moving to the UK, however: while four in ten (38%) would be happy for numbers to stay the same (31%) or increase (7%), six in ten (62%) would prefer the numbers to be reduced.

Of course, the proposal comes with a myriad of problems – not least that it may cause difficulties for employers in accessing labour and the bureaucracy necessary to show that the EU migrant has come for a job which has been advertised. On the other hand, in this day and age of the internet and social media, coming for a job, which has already been contracted for, is much easier now than in the past.

* Trinity College, Cambridge

X/Twitter

X/Twitter Email

Email